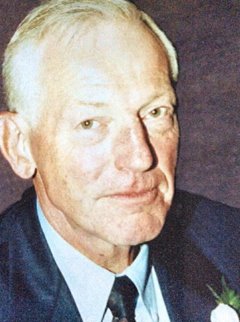

Legendary spy carries secrets to his grave: Frank Pratt

Frank Baird PRATT

(Born June 13, 1938 – November 24, 2001)

Frank Pratt would be embarrassed to be referred to as a ‘legend’.

A modest obituary records his death by cancer at age 63 at the Ottawa General Hospital on November 24, 2001. It affords no hint of his accomplished life though the pews of St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Kanata, Ontario, days later, quietly told another story. The church was filled to capacity by former intelligence community colleagues and allied intelligence officers from the Five Eyes alliance who mourned Frank’s early death and came to pay respects in acknowledgement of the significant contributions he made to the security of Canada during his storied career. Frank was as humble as he was tenacious in the pursuit of an investigation. But with posthumous apologies to this proud son of Ireland, the label “legend” fits the man.

In the annals of Canada’s substantial but little-known counter-intelligence history, Frank Pratt stands out as few others for his skills as an investigator. He was revered by those fortunate enough to work with him in investigating the many espionage cases he was assigned over his 38-year career. He was a force of nature who was to be reckoned with and who didn’t give credence to words like ‘can’t’; or ‘not possible’. As much as he demanded of those in his team, he was a generous mentor who taught young investigators the ropes and lead by his own high-energy, principled example.

Frank Baird Pratt was born in Abbeyleix, Kilkenny, Ireland on June 13, 1938. He was raised on the family farm tended to by his father and his grandfather before him. Frank and his brother James dutifully did their chores helping support the family as they attended school. Frank was a good athlete and was a member of a competitive ten-man sculling team. Years later, Frank would talk about the races and regaled how he and his mates “loved to beat the British”. After graduating, Frank was hired by Provincial Crop Driers in Kells, Meath County; an enterprise involved in the drying of grasses for the production of meal. It was at that time a relatively new business. Even at 19, Frank must have shown promise as he quickly was promoted as the firm’s Assistant Manager.

Frank’s eyes, however, were already cast on a distant horizon across the sea in Canada. He had become aware of Canada’s national police force, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and he committed himself to emigrate to Canada to join the Force.

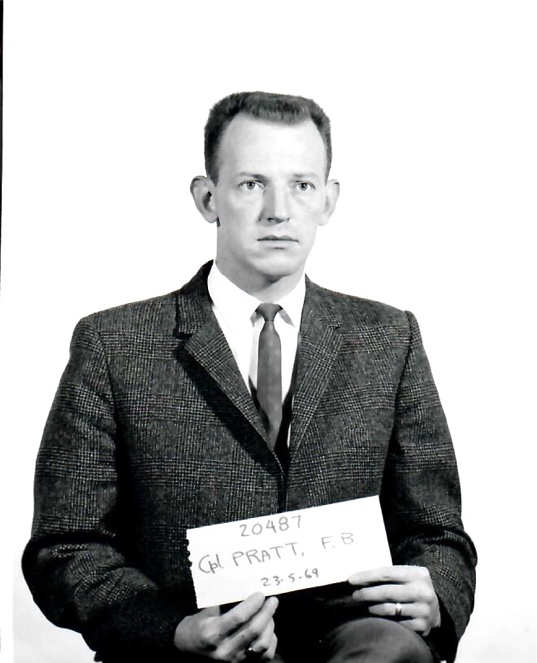

Frank sailed to Canada arriving in August 1957 without any supporting family in this new country to accept him and help him get established. He initially found residence in Belleville, Ontario where he got a job as a teller at the Bank of Montreal. In February 1958, only six months after his arrival, Frank applied to join the RCMP. On April 28, 1958, he was accepted, sworn in at Toronto, Ontario and sent to “N” Division (Ottawa / Rockcliffe) where he began 10 months of rigorous training. Much of that time was spent on equitation; learning to ride a horse. The experience had a lasting effect on Frank, and he was not enamoured with horses for the rest of his life.

After completing training in Ottawa in February 1959, Cst. Frank Pratt was transferred to the RCMP’s headquarters in Montreal where he was temporarily assigned to work in the Division’s Identification Services Section, the section responsible for fingerprints and crime scene processing.

The following month, Frank was transferred to Corner Brook, Newfoundland (as it was then known). He was assigned to the rural detachment but yearned for a more rugged environment and asked to be transferred to a remote location in an outport community. Frank’s request was accepted and in June 1959, he was transferred to the village of St. Anthony, a small community on the northern reaches of the Great Northern Peninsula accessible only by water. Despite his keen interest and best efforts, Frank was confronted with an obstacle he couldn’t overcome; a rare occurrence for him. Travelling on the detachment patrol boat in rough open water was more than his stomach could tolerate. Frank was on the move again and transferred to St. George’s and later Botwood Detachments where his police duties weren’t as reliant upon sea travel. He had his land legs and was able to focus on his work. Frank was a good police officer and by 1962 was assessed as one of the better junior members in the region.

Frank once again expressed an interest in a move, this time to the Telecommunications Branch. His supervisors assessed that Frank’s true interest was motivated by love, not work. He had met the love of his life, Florida, then living in Montreal. Frank believed a move to Telecoms would see him transferred to Canada’s mainland. His request for a transfer was accepted but, instead of Telecoms, Frank was assigned to the Security Intelligence Branch in Montreal in July 1962.

And that transfer – motivated by love – was fortuitous for Canada’s security as Frank found his second love as an investigator in the counter-intelligence field.

Montreal, then as now, was a cosmopolitan city. Several foreign consulates were located in the city and again, then as now, numerous countries used these diplomatic missions as cover for the posting of intelligence officers – spies – intent on collecting sensitive information relating to Canada. Foreign intelligence services would direct their spies to recruit agents within the government and industry to secretly gather classified information. Frank’s job was to identify those spies under cover, determine what they were after, and advise the government so that measures to stop them could be taken. Frank quickly concluded that the best way to find out what a spy was after was to recruit the spy for Canada.

Frank was highly adept at reading people, discerning their motivation, developing their trust, soliciting their cooperation, directing their actions, pushing the envelope in Canada’s interests, and being good to his word on the agreements they had struck for the cooperation afforded, often at great risk. He was more than a natural as an agent recruiter. He was gifted and successful.

Frank’s unique skills as an investigator, recruiter and operator were thankfully recognized by senior officers. They concluded rightfully that his place was on the street, not behind a desk. Barry Sheard, a valued colleague and close friend in the Montreal years, recalls that Frank was designated as a “Detective Inspector” / Senior Investigator, - a singular role assigned to Frank alone. Frank was given flexibility to pursue promising opportunities as he saw them and he offered his counsel and energies generously to the full range of counter-intelligence units, each investigating intelligence activities by different foreign states.

Frank was transferred to Ottawa in the early 1980s. He was posted to what had been the RCMP’s regional office in downtown Ottawa; “A” Division located at Bank and Cooper Streets. After the Canadian Security Intelligence Service was created in July 1984 to replace the RCMP Security Service, the Cooper Street location was re-established as Ottawa Region of the new CSIS, under the command of Ron Yaworski, Regional Director General.

Mr. Yaworski was aware of Frank’s reputation as a highly effective interviewer and he warmly welcomed Frank to his management team. In short order after Frank’s arrival, Mr. Yaworski soon assessed that Frank’s reputation was spot on. His detailed written interview reports were of high quality. Frank was as good as they said he was.

As confident as Frank was operating alone, he was open to working with a subordinate or a team and he welcomed and encouraged the camaraderie. He sought talented operators who shared his work ethic or young investigators he could mold, who held to high values and in whom he could place his trust. He was a generous mentor and spent a lot of time ensuring that you got things right.

Success to Frank was a collaborative process and his determination to succeed was unparalleled. He demanded professionalism and attention to detail by his team members and could be very stubborn when challenged. He was prepared to listen to contrary opinions, weigh them, and decide a course of action. When a decision was rendered, he carried out the plan assiduously, either personally or directing subordinates.

When Frank needed something, you knew it. Members of Frank’s team, managers whose authority Frank needed to pursue a particular avenue of investigation, or a bureaucrat in a key department (Foreign Affairs, Immigration), all came to expect the late night or early morning phone call from Frank. A clock’s only purpose for Frank was to remind him of how much time he had until the next goal he had set for himself had to be met. If he needed something done, the phone would be ringing and wouldn’t stop until the task was assigned and Frank was confident that it was being actively pursued in real time. He pushed himself hard and expected the same of his team.

A media scan will find no shortage of stories referencing Frank Pratt. He is credited in the public domain as a primary investigator in the case of Canadian academic & economist Hugh Hambleton, who served in NATO in France in the 1950s and 1960s. Hambleton was accused of spying for the KGB, the Soviet intelligence service, and was arrested at Heathrow Airport by British police upon arrival in London in June 1982. Hambleton was charged with espionage and admitted under cross-examination at trial that he was guilty. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Frank is also named in articles as a molehunter responsible for investigating allegations of the RCMP or CSIS being penetrated by foreign intelligence.

Frank was working a case in Toronto in June 1994 when he was involved in a near-fatal multi-vehicle accident. He suffered catastrophic injuries, and his survival was anything but certain. He remained in hospital for three months and began a slow, painful recovery. He retired in March 1995 and hundreds attended his farewell party at the CSIS NHQ in Ottawa to express thanks and best wishes for the future.

While he began his retirement still affected by the injuries suffered in the car accident two years prior, in 1996, Frank had to contend with an outrageous and libelous accusation levelled at him by a federal Member of Parliament, who alleged that Frank Pratt was himself an agent of Russian intelligence. The MP claimed Frank had used his position to protect another Russian agent in CSIS. The MP clearly had ambitions for greater office and her accusation against Frank clearly brought attention to her and elevated her profile. The accusations, however, were completely baseless. Frank was strongly defended publicly by CSIS and Solicitor General Herb Gray rejected the claim outright. Frank launched a lawsuit against the MP and sought a full public apology. A settlement was reached, and the MP acknowledged that she had made comments she could not support in the heat of a scrum with reporters. It was hardly a full apology and far less than Frank deserved.

Frank’s retirement was all too brief. He and his wife, Florida, travelled to Africa to spend time with Don Mahar, a close colleague with whom Frank had worked on some of his most important and challenging cases. Frank witnessed the beauty of the migrating wildlife on safari and sailed along the Nile. Amidst the glory of the continent, he also witnessed some of its worst poverty as he visited a community in Kenya that was severely undernourished and deeply compromised; an experience that Frank was very much affected by. He felt deep compassion for the villagers and the experience brought him to tears.

Frank returned to Ireland through his adult years, but those moments and memories are lost in time. He maintained contact with James, his younger brother in Ireland, through long phone calls and occasional visits. Frank’s love for and pride of Ireland were a flame that shone brightly to the end. He still retained an Irish brogue in his deep voice and had a fiery mane of red hair as a young man that held its hue well into middle age.

Frank is best remembered by his colleagues not solely for his competencies as an investigator but for his character, his passion, his energy and his compassion. Working with Frank was life-fulfilling and for some, life-changing.

Words often used in describing his character include tenacious, instinctive, irreverent, unstoppable, confident, hilarious, patriotic, proud, generous, impatient, charismatic, mentor, leader, optimist, loyal friend, dangerous adversary, son of Ireland, proud Canadian.

Frank was diagnosed with cancer in the late 1990s. He fought the brave fight but sadly this was one hill too high after an accomplished lifetime of reaching the summit. Frank died on November 24, 2001, and is buried in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police National Memorial Cemetery at Beechwood in Ottawa, Ontario.

Stewart Bell, a respected journalist then writing for the National Post, wrote an article published on November 27, 2001 – the day before Frank’s funeral - entitled “Legendary spy carries secrets to his grave”. Bell spoke with some of the former senior executives of CSIS for whom Frank had worked during his 38-year career. “He could easily be called a legend in the security intelligence business” said Alistair Hensler, a former Assistant Director. “It’s unfortunate that some of his exploits in defence of Canada will never be known”. James Warren, a retired Deputy Director, Operations said “He was tenacious. He was one of those people we call a good street man.” Speaking of Frank’s efforts to recruit foreign agents to work for Canada, Mr. Warren continued, “If we could recruit them, we recruited them and we did in some cases and that’s what made the difference. We knew more about what they were doing than what they knew about what we were doing. And it was people like Frank Pratt that made sure we did.” Former CSIS Deputy Director Rick Bennett added that Frank was “probably the greatest investigator I ever met in my 35 years in the Service.”

Frank never sought the limelight, avoided media interviews, and was not affected by the attention that his investigative work occasionally generated in the press. His storied career deserves to be told but his achievements in the world of shadows and mirrors are an elusive tale to tell. Maybe in 50 years – maybe in 100, his trials and triumphs will see the light of day. Canadians would be proud to know this man, and to know how he laboured to keep us safe and our government secure.

Canadians also owe a great debt of gratitude to Ireland for allowing us to adopt Frank Pratt and making him our own. It’s an overworn cliché that ‘we may never see his kind again’. With Frank Pratt, the cliché fits. As does the label. Legend.

Written by Ralph W. Mahar, RCMP / CSIS (Ret’d) March 17, 2023

Supported by accounts offered by Ward Elcock, Rick Bennett, Alistair Hensler, Ron Yaworski, Lucille Yaworski, Barry Sheard and Don Mahar.

References:

- Bell, Stewart, “Legendary spy carries secrets to his grave: Canadian Frank Pratt”, National Post (Toronto, Ontario), November 17, 2001, Page 5.

- Bronskill, Jim. “Spy boss denes moles in CSIS”, The Sun Times (Owen Sound, Ontario), April 9, 1996, Page 9.

- Brown, Jim., “Ex-RCMP security officer was suspected Soviet spy”, The Ottawa Citizen, May 30, 1991, Page 1.

- Canadian Press, “Reformers back away from claim of mole in CSIS”,

- North Bay Nugget (North Bay, Ontario), April 4, 1996, Page 7.

- Citizen News Service, “RCMP may testify in spy trial”, The Ottawa Citizen, December 4, 1982, Page 4.

- Macdonald, Neil, Weston, Greg, Adani, Hugh, “Hugh Hambleton: brilliance and intrigue”, The Ottawa Citizen, December 4, 1982, Page 17.

- Macdonald, Neil. “Command shakeup leaves RCMP security force reeling”, The Ottawa Citizen, January 10, 1983, Page 4.

- Mahar, Ralph, “The Pratt File; Frank Baird Pratt – A Proud Cold Warrior”, Spies in the Cemetery, CSIS National Memorial Cemetery, Beechwood, May 9, 2019.